Periodically, my parents go through spring-cleanings, finding odds and ends from my childhood. I live in a small apartment by midwestern standards (by almost any standards other than New York City standards), so I have scant space.

Periodically, my parents go through spring-cleanings, finding odds and ends from my childhood. I live in a small apartment by midwestern standards (by almost any standards other than New York City standards), so I have scant space.

Nearly seventeen years ago, I packed a bunch of boxes in a car with two dear friends and we drove from Detroit to New York City. Ever since, through all manner of life changes, through moves from Brooklyn to Hell’s Kitchen to Queens, I have made promises to my parents that I will collect some of these childhood belongings, if they please-please-please keep them for me.

And my parents are very understanding and occasionally just send me manageable boxes of the various detritus of my upbringing—usually charming madeleines: drawings, much-loved books, odd little miniatures and strange collections I don’t even remember starting, or ending (how did I end up with all those miniature ceramic animals? the boxing monkey figurine?).

A few weeks back, one of these boxes contained a slender volume I had no memory of for a moment. Until I did. It is entitled, The Clue Armchair Detective by Lawrence Treat and illustrated by Georgie Hardie, with the subheading: Can You Solve the Mysteries of Tudor Close?

Essentially, it’s a game/activity book or, as the cover rather awkwardly poses it, “A Packed File of Mystery Puzzles for All the Family.” And it is one of many tie-in books related to the game Clue, which I’m sure is why my parents bought it for me originally, circa 1983.

It opens with a letter to the reader,telling us we are “cordially invited to help solve the mysterious death of Humphrey Black, found brutally murdered in his house, Tudor Close.”

What follows is a series of more than 25 separate “suspect files,” which are really individual mystery pages where, if you look closely enough, you should be able to solve these individual crimes (theft, vandalism, murder) and, ultimately, the central mystery of who killed Humphrey Black. The answers lie on the last pages.

And as I turned the pages I remembered staring at those puzzles, had this sense memory of which pages captivated me most. It lacks the hauteur of my memories of Clue, and the whole Clue/Agatha Christie/murder at the estate vibe. Not that that’s absent (or that Agatha Christie is all hauteur) but the book is so much weirder than that.

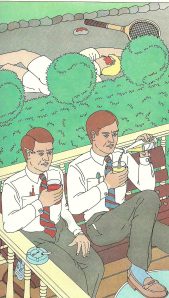

Sheeted corpses, bathtub deaths, yes, but also a mounted fish stuffed with “chips.” Eerie blank-eyed twin brothers. A kidnapped boy who looks stunningly like Bobby Franks. A man in drag with the uncanny stiltedness that sings: Brian De Palma movie. (In fact, an overhead surveillance shot that also recalls De Palma!) Witchcraft. Voodoo. A particularly unnerving scene of a raucous pub brawl, where one lipsticked woman sits, staring fixedly at the ceiling…at what?

It’s funny, touching something your memory effectively erased. I can’t imagine ever remembering this book any other way than touching it. And yet it’s an access point, another tunnel in.

It’s surprising when we are sure we know the touchstones that were important to us as children—the books that stunned and enthralled us, the movies that flutter in our brain.

But I wonder if it’s the things that made less a clear mark, whose connection is more tentative, whose role is less transparent—might they matter more? Might these lost memories or totems—unedited by the parts of ourselves that insist we know ourselves so well—be the things that tell us the most?”

As the letter to the reader closes:

All will be revealed once you read the last answer. If you’ve solved the mystery correctly, give yourself a pat on the back. If not, resolve to do better next time. Then move onto the next case.

Good Luck!