Author’s Note 10/22/18: To the relative who asked me to remove this inherently incomplete and admittedly harsh essay, a polite no. If I start unpublishing everything I write that offends someone, there won’t be anything left. I think my brilliant, contrarian uncle would be okay with that.

Author’s Note 10/22/18: To the relative who asked me to remove this inherently incomplete and admittedly harsh essay, a polite no. If I start unpublishing everything I write that offends someone, there won’t be anything left. I think my brilliant, contrarian uncle would be okay with that.

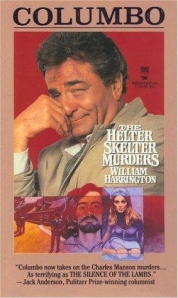

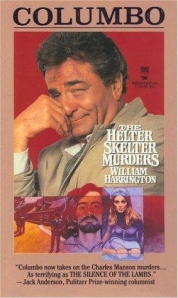

I’ve been thinking lately about a writer I can pretty much guarantee none of you have ever heard of – William Harrington. He wrote or ghostwrote twenty-five novels, including many of the Washington thrillers of presidential spawn Margaret Truman and Elliott Roosevelt, novelizations of the “Columbo” series, several Harold Robbins novels, and his own thrillers. In the New York Times, Anatoyle Broyard praised his clean writing and research.

Like a lot of dead writers, Bill Harrington is pretty much forgotten. But he was my uncle and the only writer I knew when I was growing up, so he holds a special place in my pantheon. His story proves that writers make terrible relatives and worse role models. You’ll see why soon enough.

I remember Uncle Bill as a demi-god of 1970s New York City, a manly man who flew his own plane into Teterboro for long lunches at La Grenouille with his agent and Terry Southern. Velvety suits with wide lapels, plates of duck a l’orange and flaming crepes for dessert. Plenty of Chablis all around. Bordeaux from the fine 1970 vintage. Nights with Peter Falk at the Playboy Club on East 59th.

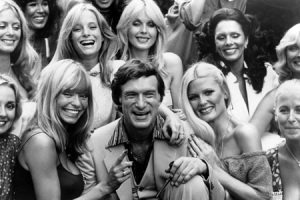

I’m making most of this up, of course. But that’s probably the life he had in mind – like Hef, Harold Robbins, Burt Reynolds, and Esquire men.

The real Uncle Bill was often charming and occasionally mean but it was excusable because he was a writer, and so, insecure and deeply flawed. He looked like a pocket-sized Norman Mailer, without as much genius or popularity but with an extra dose of street smarts. Bill inspired a kind of fearful awe in our family because he was pretty much always half-drunk and prone to conversational bullying.

Bill took great delight in turning any family occasion into a debacle, which I appreciated, kind of:

Florida, 1968–Family vacation. We climb a tower at a scenic overlook. When everyone else is climbing down, Bill grabs me by the ankles and hangs my scrawny, seven-year-old ass, Pip-like, above the Everglades. When I scream and squirm like a psychotic shrimp, he tells me now you know what if feels like to be scared.

Cincinnati, 1974–Thanksgiving Dinner. Uncle Bill waves me forward from across the table. But instead of asking me to pass the sweet potatoes, he says Have you tasted your own sperm yet? He gives a wan smile as if a special treat awaits me. Then snorts into his Scotch.

Columbus, 1977–Some college bar. The place is empty and no one else in our family is drinking since it’s about noon. But Uncle Bill is marinating in Scotch. To shock us, he’s going on about homosexuality. He says he might suck a cock but definitely wouldn’t let someone fuck him up the ass. As if. By then he looked like Larry Flynt, with a big muff of smokebush hair waving over his gray eyes and a potbelly that begged for luggage wheels.

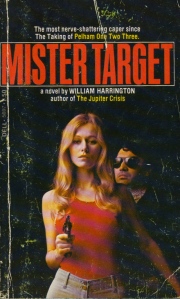

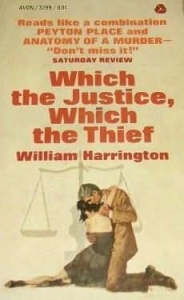

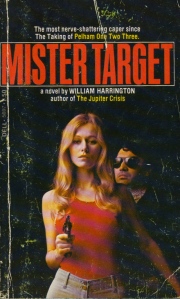

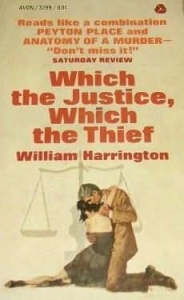

Each Christmas, like a pulp fiction Unibomber, Uncle Bill would sign his latest hardcover and mailed it to my straight-arrow father, who hid Bill’s books in the Siberian reaches of the knotty-pine bookshelves of our den. Unbeautiful and chunky, Bill’s books were hyper-commercial and smelled of cheap paper and ink, like gun catalogs. Mister Target. An English Lady (his hit). The Search for Elizabeth Brandt (not sure what that one’s about). Virus (a computer thriller before anyone owned a computer). Trial (an early legal thriller).

Left alone at home, I would pull over a chair and climb up to retrieve one of Uncle Bill’s reputedly dirty novels, seduced by their inky perfume. When I was about ten, I turned to a scene about a devious pervert who had gathered up a thin gay junkie and a busty young whore – and forced them to wear scuba suits while having sex for his amusement. Then, much to their surprise (and definitely to mine), the devious pervert plugged in a hidden cable connected to electrodes in the scuba suits and ffffssssstttt.

Left alone at home, I would pull over a chair and climb up to retrieve one of Uncle Bill’s reputedly dirty novels, seduced by their inky perfume. When I was about ten, I turned to a scene about a devious pervert who had gathered up a thin gay junkie and a busty young whore – and forced them to wear scuba suits while having sex for his amusement. Then, much to their surprise (and definitely to mine), the devious pervert plugged in a hidden cable connected to electrodes in the scuba suits and ffffssssstttt.

They were electrocuted via their smoke-spewing pudendum!

I closed the book. This was sex, which everyone seemed to want to do? Where was I going to find a scuba suit? And what about those devious perverts and their electric cables?

My worldview was twisted forever.

Lest you think he was just a garden-variety sick pup, Uncle Bill was a technology savant if not a literary giant. He was a successful attorney and avid pilot. He wrote provocative editorials and orchestrated media confrontations. He co-developed the pioneering LEXIS database, which evolved into an information service that lawyers rely on every day.

That said, he was also a very sick pup.

I had dinner with Bill spring of my senior year in college, hoping for advice for a young writer about to venture out into the marketplace. What I got instead was an evening-long, soul-killing rant about his huge book advances, celebrities he knew, and how bad most other writers (Harold Robbins!) were.

Harold Robbins and friends

After dinner, which included drinking most of the red wine in southern Connecticut, my ursine uncle padded off to his study to write. I could barely walk but Uncle Bill was writing, or appeared to be. My last memory of that night? His puffy face and glittering eyes lit green by the screen of his expensive PC, the first I had ever seen.

There goes a pro, I thought at the time, too young to recognize a drinker with a writing problem. After that, I lost touch with Uncle Bill on purpose, trying to avoid contagion from the palpable bitterness that pumped through him like central air.

Then in 2000, Uncle Bill walked out the front door of his Greenwich mini-mansion and blew his brains out with his fancy German pistol. “William G. Harrington, a mystery novelist with a long career as a collaborator with celebrity authors, died at his home in Greenwich, Connecticut,” the Times obit duly recorded. “The police said he apparently committed suicide, writing his own obituary before he died. His writing career spanned 37 years.” They didn’t run the obit he wrote, of course.

I have to assume that it wasn’t drinking that killed Uncle Bill, or divorce, or declining talent. It was corrosive disappointment. I see his sad but not necessarily tragic life as a cautionary tale for writers – of serious money earned and respect denied, talent accrued and squandered, very good deals followed by deals with the Devil, novels thick with cops and soldiers that led to a final tale of a Luger in his own pale, shaking hand.

Writing is a decathlon of disappointment, even for writers who do well at it. Talk to most writers and they’ll tell you about the major film interest that almost happened but didn’t, the deal with Knopf that went south, the novel that never found a publisher, the foreign rights that floundered. Writers collect disappointment like normal people collect lint.

When my father died a few years ago I took his stack of Uncle Bill’s novels to Goodwill in Montgomery, Ohio and dropped them off with the other debris from the basement. It took three or four trips from the Buick. I never even thought about keeping one of his books. They were bad voodoo, tainted by Bill’s Scotch-scented paw. If I had thought about it, I probably would have burned the books just in case. Their dense, heavily foxed pages would have made a nice blaze in the woodstove for an evening.

A jumble of thousands of books lines the walls of our house – writers I revere or not, books that serve as beacons of brilliance or warning lights, novels I don’t particularly like written by friends I do. When it comes to books, we’re non-denominational. So why didn’t I just put Bill’s up in the outer reaches like my father used to, as a top-shelf memorial to the other writer in the family?

Because they were reminders of something few writers (or people, generally) want to know: Most of our big plans for ourselves probably won’t happen.

Still life with bunnies

Even for Uncle Bill. Trolling through louche 1970s New York City, getting hired to write for big money, living in his Cos Cob mini-mansion with a fluffy dog named Easy (for easy lay; the dog was a slut and Bill sexualized everything) – it all never quite added up to what he had in mind. So he wound up dead. And not happy dead, surrounded by loved ones in a hospice or slipping off at 92 in his sleep. He died alone on his doorstep, brains on the lawn, Luger in his hand, as two-dimensional an ending as any he ever penned.

Writers create people out of words. So why shouldn’t we create expectations out of some version of talent, the occasional break, and bits of praise? The trajectory leads ever upward. Except when its doesn’t. How we deal with the inevitable disappointments seems to make all the difference between a writing life and a bitter end.

A couple of weeks ago I made some truly half-assed attempts to track down Uncle Bill’s agent, lawyer, and other remaining cohorts. But when I heard their tired voices on my voicemail I didn’t have the heart to call them back and dredge up what I’m certain would have been mixed memories of the late William Harrington, American novelist.

A couple of weeks ago I made some truly half-assed attempts to track down Uncle Bill’s agent, lawyer, and other remaining cohorts. But when I heard their tired voices on my voicemail I didn’t have the heart to call them back and dredge up what I’m certain would have been mixed memories of the late William Harrington, American novelist.

I could have called my aunt, who plays piano bars down in Florida, or my cousin in Arkansas. But we’ve been out of touch for years and pestering them about their dead husband/father didn’t seem like a particularly kind way to get reacquainted.

So I didn’t make the calls or do the legwork. I cared but not that much. I already know what I need to about Uncle Bill. And now so do you. Bill Harrington was a writer who fooled himself until he couldn’t anymore. He was a good father and a perverse uncle. He lived high and died low. He was incredibly smart and sharp. He wrote and published twenty-five books.

We should all be so lucky. Right?

For an intro to Stona, click here.

Author’s Note 10/22/18: To the relative who asked me to remove this inherently incomplete and admittedly harsh essay, a polite no. If I start unpublishing everything I write that offends someone, there won’t be anything left. I think my brilliant, contrarian uncle would be okay with that.

Author’s Note 10/22/18: To the relative who asked me to remove this inherently incomplete and admittedly harsh essay, a polite no. If I start unpublishing everything I write that offends someone, there won’t be anything left. I think my brilliant, contrarian uncle would be okay with that.

Left alone at home, I would pull over a chair and climb up to retrieve one of Uncle Bill’s reputedly dirty novels, seduced by their inky perfume. When I was about ten, I turned to a scene about a devious pervert who had gathered up a thin gay junkie and a busty young whore – and forced them to wear scuba suits while having sex for his amusement. Then, much to their surprise (and definitely to mine), the devious pervert plugged in a hidden cable connected to electrodes in the scuba suits and ffffssssstttt.

Left alone at home, I would pull over a chair and climb up to retrieve one of Uncle Bill’s reputedly dirty novels, seduced by their inky perfume. When I was about ten, I turned to a scene about a devious pervert who had gathered up a thin gay junkie and a busty young whore – and forced them to wear scuba suits while having sex for his amusement. Then, much to their surprise (and definitely to mine), the devious pervert plugged in a hidden cable connected to electrodes in the scuba suits and ffffssssstttt.

A couple of weeks ago I made some truly half-assed attempts to track down Uncle Bill’s agent, lawyer, and other remaining cohorts. But when I heard their tired voices on my voicemail I didn’t have the heart to call them back and dredge up what I’m certain would have been mixed memories of the late William Harrington, American novelist.

A couple of weeks ago I made some truly half-assed attempts to track down Uncle Bill’s agent, lawyer, and other remaining cohorts. But when I heard their tired voices on my voicemail I didn’t have the heart to call them back and dredge up what I’m certain would have been mixed memories of the late William Harrington, American novelist.