Image via Wikipedia

In an earlier post I wrote about how, despite growing up in one of the book capitols of the universe, going to a fancy private school, and living with parents who may be the only people I know who own more books than me, few books, shows, or movies made quite such an impact on me as trashy stories of kids who moved to New York City and fell into trouble. And that trouble was usually prostitution, drugs, or both. But it was prostitution that was the biggest threat–you could go to rehab for drugs, but you could never wash off the stain of having sold yourself. Iris in Taxi Driver. Christiane F. Angel. A dozen after-school-specials. Tootie’s encounter with a teen prostitute on The Facts of LIfe (thanks, google!). Dawn, Portrait of a Teenaged Runaway. Go Ask Alice. Mary Ellen Mark‘s haunting Streetwise. Thousands of made-for-tv movies, hundreds of paperbacks, a million low-budget exploitive/educational flicks. From 1976-84 (somewhat arbitrarily), teen hookers seemed to be taking over the world. Or at least New York City.

What was the late seventies/early eighties obsession with hookers, especially young ones, all about? Let me be clear here that I am in no way talking about the lives of real prostitutes (of course, most street prostitutes have short life spans and come from a history of physical and sexual abuse and poverty and few options, while a small minority of working girls choose prostitution willingly as their chosen career). I am instead talking about the mythologized prostitutes, especially children, who came to us through popular culture (and also not-so-popular culture). It wasn’t just trashy runaways in Times Square–look at Louis Malle‘s Pretty Baby, for example.

To paraphrase something Megan said the other day, what were the eighties trying to tell us with these stories? I just re-read Steffie Can’t Come Out To Play, one YA teen-hooker tale that has kept with me all these years. I read this book entirely too young, maybe ten or eleven. A Publisher’s Weekly blurb inside the cover gives you a hint about the teen-hooker obseesion of the era:

“Let’s hope it won’t be banned where so many cautionary tales are, right where they could do the most good–in small towns where girls of Steffie’s age [14!], hardly more than children, leave home in droves for reasons like hers and fall into the same sordid trap.”

Really? 14-year-olds were leaving respectable small-town homes in droves to become Times Square hookers? I don’t think the statistics exactly bear that out. I think there was a big dose of denial in this child-hooker hysteria–a denial of the reality that there were children who were indeed prostituting themselves, not because they felt like leaving their happy home on a whim, but because life had dealt them a very raw and unfair hand. There are now a lot of homeless children and teenagers in the Bay Area, where I live. Almost everyone I know denounces these kids as “fake,” whatever that means. It causes us pain when we see people in need and don’t help, so we make up elaborate stories to counteract that pain–those young homeless prostitutes have all kinds of options, they’re just spoiled brats!

But then, why the media obsession? Let’s look at Steffie: Steffie is from Clairton, PA, apparantly the worst place in the world. “Clairton, Pennsylvania is a black-and-gray town. Even though most of the steel mills are closed now, you still can’t get rid of the black and gray.” Stephanie takes care of her parents, her pregnant sister, and her little brother, cooking, cleaning, and constantly wiping soot off the walls, with no end in sight. Who’d want to stay? I wouldn’t. She dreams, absurdly, of being a model, so she gets on a bus and goes to New York City. In NYC, she is almost immediately picked up by a pimp named Favor. Favor is insanely wealthy–three Cadillacs with custom-made hood ornaments, fur coats, giant apartment, gold jewelry, cash falling out of his pockets. Steffie and Favor have a whirlwind courtship (“I just kept shaking my head, imagining how lucky I was, running into this beautiful man so quickly, as soon as I got here!”) after which, you guessed it, there’s a price: “‘It’s not a free ride for you, baby,’ he said, shaking his head slowly. ‘You want a whole lot of nice things … you have to earn them. Everybody does…'”

We will set aside how oddly reminiscent this line is of Debbie Allen’s famous bon mots from Fame, the TV show (“Fame costs, and right here is where you start paying–IN SWEAT.” And of course Cocoa in Fame, the movie, had her own teen-porn storyline.) So, Steffie becomes a prostitute. Which basically means a few yucky minutes a day and the best outfits EVER. Sex in this story, as in many teen hooker stories, is glossed over to the point of not existing. By the end of the book you get the impression that being a teen hooker is more about having the best clothes than about actually having sex. There’s usually a few sordid moments that highlight the young lady’s extreme desirability (the girl in question is almost always a top earner, not just any old hooker) and maybe one or two scenes of erotic and interesting kink, but rarely any actual sex (the “dirtiest” scene in Steffie involves the highly attractive and eroticized Favor watching her get dressed).

But listen to Steffie describe a shopping trip with Favor, a reward for her first trick (which she’s entirely forgotten, hazy as it was to begin with): “It was lovely and fun!…He bought me French jeans. They were skintight and looked wonderful. And he bought me a short skirt that looked like it was made of leopard skin and felt like it, too. And shorts the same material. And another skirt and another pair of jeans in a different color and a pair of high silver boots that came all the way up to my knees practically. They were the most fabulous things I’d ever seen. And they had high heels, too.”

Dipping back in, I’m struck that these books and media made being a teen hooker seem like basically the best life in the world. Lots of cash, attractive pimps, glamorous lifestyle, and all those clothes. Hot pants and high heels, halter tops, miniskirts, spandex. Can I still apply for this job? And is it possible what we thought was a sexual fixation was really a clothing fixation? Later, Steffie meets a hooker even younger than her in a jail cell and they compare boots. Even Christiane F., who was an actual child prostitute, devotes pages of her autobiography to her tight jeans, slit skirts, garter belts, and, of course, boots.

Another focal point of teen-prostitution stories seems to be the interactions among the girls themselves. Christiane F. devotes page after hypnotic page to gossiping about her cohorts. Angel, if I remember right, is on a mission to avenge the death of a friend. And Steffie’s downfall, ultimately, is not the grown men she has sex with, it’s the other hookers, who don’t like her. The teen hooker is in many of these scenarios in danger of being cut, scratched, pinched, or otherwise unkindly invaded by older prostitutes. I think there is something very telling in there about our relationships with our mothers, aunts, sisters and teachers–especially the way they can sometimes force entry into our very own bodies.

But back to Steffie. Steffie pisses off the other hookers for being younger and prettier (none of us have ever experienced THAT, right ladies?), a cop takes an interest in her and beats up her pimp Favor, and she’s thrown out of the stable with, tellingly, only the suitcase of awful clothes she brought with her from Pennsylvania: “Nothing else. None of my new jewelry, none of my new coats or jackets, nothing. The only new things I had were what I was wearing: jeans, a blouse, sandals. Even my pairs of boots weren’t there, Just my old clothes … my old Clairton clothes. My blue dress for Anita’s wedding … my old pumps…” (All these ellipses, by the way, are in the book.) A cop points her toward a Convenant-House type place (minus the pedophiles, we hope) and the kind if frightful people there help her get home.

“There wasn’t any other place in the world for me to go. I really didn’t have any choice. But oh, I wanted to put it off. Just picturing actually being there … in my own house … made my stomach turn over.” Well, the thought of Steffie back in Clairton wiping soot off the walls kind of makes my stomach turn over too. Being a hooker didn’t work out for her, but don’t we have some better options? Couldn’t she, I don’t know, go to college? Learn a new skill? Go on an adventure?

And I think that might, ultimately, be the point. Life in the seventies and eighties was often grim. Us girls didn’t have all the options we have now. (And I’m not saying things were so great or even any better for boys–you had and have your own set of problems, but that’s for you to write about.) I can’t think of a single female writer we read in school other than Jane Austin and maybe a little Charlotte Perkins Gilman. I’ve written before about my obsession with Three’s Company, where the pretty women bordered on deaf-mute (and we’re not even going to talk about the horrifying specter of Mrs. Roper). Being pretty and smart was not on the program and niether of those options, frankly, was too appealing to being with. You could be the smart girl and spend you life buried in books and never have sex or you could be the pretty girl and be the deaf-mute object of desire, but at least you got to leave the house. The teen hookers in books and film were well-dressed and glamorous and tough and worldly and experienced and (Steffie aside) smart. They were no dummy like Chrissy or Farrah, and they weren’t boring like Janet or Sabrina. They wore bright colors. They had fun. They had sex. They knew things.

In the end, I think these mythologized child prostitutes were a spot our culture found to release the pressure of seventies grimness and limited choices and find something new–a new way of looking at girls, a new way of being in the world, and most of all, maybe, a new way of dressing–that is, a new way of describing ourselves, as women and girls, and showing ourselves to the world. I think our teen hooker obsession–mine personally and ours culturally–isn’t really about sex. I think it’s about clothes and how women treat each other and what we do with our lives and how we make choices and the perilous times and good outfits that await us when we deviate from the plan and “run away from home.” We are often faced with a choice in life: safe, or interesting. I think our mythology of teen hookers is a mythology of choosing “interesting,” and I think the mythology tells us that we may not come out so clean and pure, but we can still come out of it wearing our favorite boots. And that’s pretty good, I think.

(Photo Courtesy of Sunny Down Snuff)

(Photo Courtesy of Sunny Down Snuff)

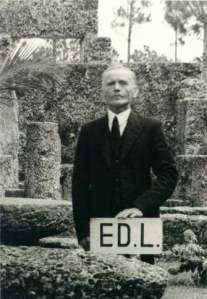

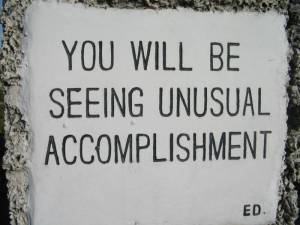

While, in that part of Florida, coral can be 4,000 feet thick, Leedskalnin reportedly used only hand-made tools, with no large machinery and no workers assisting him. Among much of the disbelieving press about the Castle—particularly during its early years—much nasty head-shaking was made not just over the fact that one man could build something like this, but that an “illiterate immigrant” could. According to the Castle’s official website:

While, in that part of Florida, coral can be 4,000 feet thick, Leedskalnin reportedly used only hand-made tools, with no large machinery and no workers assisting him. Among much of the disbelieving press about the Castle—particularly during its early years—much nasty head-shaking was made not just over the fact that one man could build something like this, but that an “illiterate immigrant” could. According to the Castle’s official website: The best part of the story, though (for me), is not the triumph of one dedicated (obsessive) man to overcome expectation, engineering, and our conceptions of what’s possible (though that’s pretty good too). It’s the reason why Mr. Leedskalnin built the castle to begin with. I bet you know why.

The best part of the story, though (for me), is not the triumph of one dedicated (obsessive) man to overcome expectation, engineering, and our conceptions of what’s possible (though that’s pretty good too). It’s the reason why Mr. Leedskalnin built the castle to begin with. I bet you know why. Mr. Leedskalnin never married. While he extended invitations to Agnes Scuffs over the years, she never did see the monument he built for her.

Mr. Leedskalnin never married. While he extended invitations to Agnes Scuffs over the years, she never did see the monument he built for her.