On book tour of late, I visited Michigan and, for the first time, talked about my novel, The End of Everything, in the world that inspired it—suburban Detroit. It was a strange feeling, seeing many old friends stretching as far back as elementary school.

After the reading, a trio of these friends—three women, all looking incandescent despite the humid weather and the clambering hands of their downy headed children—came up to say hello and pointed out that I had in fact used the actual names of my high school chemistry teacher and middle school math teacher (both unusual names) in the novel.

I can’t account for the fact that I’d forgotten this entirely, can’t even say I was ever aware I’d done it. It was an uncanny feeling, like being caught. Like a dream when someone says to you, “I was just on the third floor of your house” when you know you only have two floors.

This episode was followed by an after-party in which several folks, including Eric Peterson, asked if my novel was inspired by the Oakland County missing children cases of the late 1970s. I am, let it be said, a true-crime junkie, which is why I cannot rightly explain the blank face I gave in return. What missing children?

Because my novel is centered around a missing girl, I have spent the last several weeks talking about missing-children cases (with both tragic and happy endings) virtually everywhere I go. One of the reasons I set the novel in the early 1980s was because I remember distinctly the changes in my community in terms of child safety. After the Adam Walsh case (1981), I remember a distinct feeling of hysteria over “stranger danger” and the way that made me feel as a kid. To me, everything felt like an enticing, half-hidden mystery. But to parents, teachers, everyone else but we kids, it felt quite intensely like a place of peril, especially to children.

So, as I’ve visited bookstores, others have shared similar tales of the Walsh case, and other ones. I know for Sara, the Etan Patz case in New York had a similar impact. And, amid all this, there was both the terrible Brooklyn case and the Caylee Anthony phenomenon (what do you do when the danger is within your own home, which, statistically, is usually the case?).

Amid all these conversations, though, I continually asserted it was the Adam Walsh case that I remember so vividly, in large part because everyone saw the TV movie and the graphic details of Adam’s death scattered through our school with abandon.

But an Oakland County case? I didn’t recall it one bit.

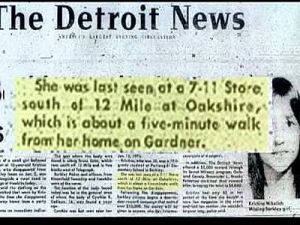

For some backstory, I grew up in Wayne County (Detroit lies at its heart and my town, Grosse Pointe, serves as its upturned chin), the direct neighbor to Oakland, where we might go, when I was a kid, to the movies, or their mall. From what I’ve since learned, over a 13-month period in 1976-1977, four children (ages 10-12) were abducted, held for several days, and murdered. In the grim way of media spectacle, the perpetrator was dubbed the “Baby Sitter” because he kept the children alive for as many as 19 days, feeding them and bathing them before killing them. No one was ever convicted, though there are strong beliefs in the identify of the perpetrator.

I would have been five or six at the time, which is probably why I don’t remember them as they were occurring. But not even in the intervening years?

At the after-party, when discussion of the case came up, I asked my dad if he remembered the case.

“Oh yes,” he said, “of course.”

I’s so interesting because clearly, as a child, I must have felt it—the sense of attenuated fear, anxiety, terror. The dread that must have stretched for years with no suspect found, no justice served. In fact, especially in light of new DNA analysis, there continue to be stories (and stories) about the case, as recently as two weeks ago.

But I have no conscious memory of the case at all. And yet how much it must have impacted all our lives. Both my brother and I just five years younger than the Oakland County children, abducted in daylight, after buying candy at a pharmacy, coming back from the 7-11.

I am sure my parents shielded me from the specifics, and I do remember all the steps taken in my elementary school to alert parents to “stranger danger.” And I remember afer one such school assembly being particularly frightened to walk the single block home. But as much as I recall countless other missing child cases, I never, ever came upon the one in my own backyard.

It makes me wonder how much I did know about the case, in whatever ways a five or six year old can, but somehow I forgot it, the way we forget things we want to, need to.

I should add, The End of Everything bears no similarity to what happened in Oakland Country, in facts large or small. I can’t say I even consider it to be a novel about a missing child precisely, but instead about an enchanted family and the power we invest such families with. But it is inspired by that feeling so specific to the late 70s-early 80s. The sense of the world changing, abruptly, even over night, because all the adults were suddenly terrified and that terror painted the entire world of my youth (many of our youth’s) with a powerful menace. The message was: You are not safe, and you never were.

But even adult fear couldn’t stop us. We still needed to discover, to push through to adulthood, to find, on our own, the peril and beauty of the world. We did.

And hat tip to Eric Peterson, who first suggested a connection between my book and the case and who provided great insight into the case that night.

Sunday’s New York Times ran an interesting piece that speculated about why Hollywood seems to have so few (and even fewer successful) movies with preadolescent girls (roughly ages nine to 14) at the center. While the book market for this age group is booming, the carryover to film has been far less reliable. While movies like 13 certainly depict the perils (in a way that reminded me mostly of the best art-directed after-school special ever) of the age, this article focuses instead on movies targeting preadolescent girl viewers.

Sunday’s New York Times ran an interesting piece that speculated about why Hollywood seems to have so few (and even fewer successful) movies with preadolescent girls (roughly ages nine to 14) at the center. While the book market for this age group is booming, the carryover to film has been far less reliable. While movies like 13 certainly depict the perils (in a way that reminded me mostly of the best art-directed after-school special ever) of the age, this article focuses instead on movies targeting preadolescent girl viewers. One of the films mentioned in the piece as a rare positive example is

One of the films mentioned in the piece as a rare positive example is  When I was nine the “teen sex comedy”

When I was nine the “teen sex comedy”  I never read much young adult fiction, and there certainly weren’t a fraction the number of YA novels as there are today (nor the array of options within them). As a result, with the notable, stirring exception of Flowers in the Attic (and, of course, Judy Blume), I jumped to adult books, which promised a peek into the grownup world for which I was unprepared (sex ed courtesy of John Irving and

I never read much young adult fiction, and there certainly weren’t a fraction the number of YA novels as there are today (nor the array of options within them). As a result, with the notable, stirring exception of Flowers in the Attic (and, of course, Judy Blume), I jumped to adult books, which promised a peek into the grownup world for which I was unprepared (sex ed courtesy of John Irving and  Duncan’s books felt dark, strange, taboo—much like V.C. Andrews. Except when you read V.C. Andrews, you feel the frantic, sexed crazy on her. And her world is very foreign from yours (I didn’t know any girl imprisoned in the attic of a mansion, starved and tortured and whipped by mother and grandmother, dangerously beloved by her own very handsome brother), which is part of their appeal. It’s total, compulsive, dirty fantasy.

Duncan’s books felt dark, strange, taboo—much like V.C. Andrews. Except when you read V.C. Andrews, you feel the frantic, sexed crazy on her. And her world is very foreign from yours (I didn’t know any girl imprisoned in the attic of a mansion, starved and tortured and whipped by mother and grandmother, dangerously beloved by her own very handsome brother), which is part of their appeal. It’s total, compulsive, dirty fantasy. In Stranger with My Face, teenage Laurie Stratton is haunted by the presence of another, someone who looks just like her. Laurie—whose dark features never matched her family’s sunny ones—turns out to be adopted, permitting full play of pre-adolescent and adolescent fantasies of orphanage and mysterious ancestry—and a reason for feeling different, out of place. When her dark double first appears, it’s a moment that, for me now, gives me the same spiky shiver and horror I experienced when first reading Sara’s magnificent Come Closer:

In Stranger with My Face, teenage Laurie Stratton is haunted by the presence of another, someone who looks just like her. Laurie—whose dark features never matched her family’s sunny ones—turns out to be adopted, permitting full play of pre-adolescent and adolescent fantasies of orphanage and mysterious ancestry—and a reason for feeling different, out of place. When her dark double first appears, it’s a moment that, for me now, gives me the same spiky shiver and horror I experienced when first reading Sara’s magnificent Come Closer: There is not even space enough to talk about what was my favorite Duncan novel,

There is not even space enough to talk about what was my favorite Duncan novel,

Then, a few days ago, I saw some writer mention Edith Nesbit’s

Then, a few days ago, I saw some writer mention Edith Nesbit’s