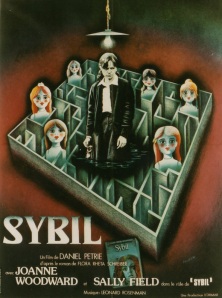

For a time, when I was a kid, I was obsessed with the book (and movie) Sybil by Flora Rheta Schreiber, which famously told tale tale of “Sybil,” the psyeudoynm of a young woman treated by Dr. Cornelia Wilbur for what the doctor came to feel was multiple personality disorder (now called dissociative identity disorder) .

At around age ten or eleven, the TV movie must have been re-run because I remember many conversations with girls at school, detailing with giddy horror, the terrible punishments Sybil underwent under her psychotic mother’s care, or so the movie relayed. It’s funny to think of it now–I’m embarrassed the palpable excitement we all seemed to feel in the particularly lurid details of the punishments. But it was the nervous laughter of coming upon something deeply secret, or a taboo, or something maybe like our own darkest Grimms-spun nightmares of abuse at the hands of our parents. (If you read Flowers in the Attic, consider the many titillating scenes of maternal and grandmaternal abuse and you will see this particular childhood fascination in full bloom.)

But I wonder if a key part of my interest in the book, as in many books like it (Three Faces of Eve, I Never Promised You a Rose Garden) that focused on women in mental health crises, was the notion that these books conveyed something about womanhood that I may have been uninterested in hearing through plainer vehicles (e.g., a book on a female hero, or even feminism!).

The reason I ask is that I recently read an advance copy of Sybil Exposed: The Extraordinary Story Behind the Famous Multiple Personality Case by Debbie Nathan, which comes out in October. It is an utterly riveting, troubling and troubled book that traces the intertwined fates of the real Sybil (her identity was finally revealed in the 1990s), Dr. Wilbur and the author of the original Sybil, Flora Schreiber. And it is a harsh exposé that calls into question nearly every aspect of the original book and certainly every aspect of Dr. Wilbur’s treatment of her patient (which apparently involved daily injections of “truth serum” to such a degree that her patient became a full-blown drug addict).

Without getting into the specific charges raised within, Sybil Exposed also stands as a fascinating study of what is was like to be a woman in the midcentury—in particular women who chose alternative paths, or for whom those paths chose them. The book description notes:

Exposing Sybil combines fascinating, near mythic drama with serious journalism to reveal what really powered the legend: a trio of women—the willing patient, her devoted shrink, and the ambitious journalist who spun their story into bestseller gold.

That trio of women at the center of the book all suffered mightily under the professional and personal limitations that their era (1940s-60s). Sybil, struggling with mental health issues (mostly, obsessive compulsive disorder, as we might see it now) that were poorly understood in her small town and within her strict Adventist faith, fought the threat of poverty, a sense out outsiderness and strong stigma. Dr. Wilbur faced the challenges of being one of very few women psychiatrists, coming up at a time when female patients much less female doctors faced strong bias and sometimes abuse. And the book’s author Flora Schreiber spent decades trying to make her name in journalism, to move past the women’s magazine gossamer she was repeatedly hired to spin in favor of something meatier, more significant. Something big.

One can see the crucible stirring. To Nathan, the result was Sybil, Inc., a multi-millionaire dollar business built on a foundation of lies. (Or, at the very least, well-meaning fabrications and half truths.)

Tracing these women’s paths and their crossing—the way their lives interlocked as they became enmeshed (and enmeshed themselves) in something far beyond their dreams or their capacity to control—it is spellbinding. But the response to the original book and movie is perhaps the best part of the story. Thousands of mostly female readers writing letters to all three women for years about how Sybil spoke to them, about how they too felt they were divided into two, three, four or more women. How they too felt split, divided. Lacking a center, a self.

Much like the women in the 1950s, facing that era’s constructions, made Three Faces of Eve a best-seller, the women of the 1970s, living amid a time of dramatic social tumult and changing gender expectations, Sybil struck a nerve. (And while, according to Nathan, the vast majority of those who wrote to Schreber were women, one can see the appeal across many populations, all of whom face constricting social expectations, the pain of feeling you must wear different masks through life.)

Maybe (probably) this is a massive justification for my own dark childhood reading habits, but I wonder now about we school girls tearing through Sybil’s pages behind locker doors. I wonder if it wasn’t just the sharp horror of tales of abuse (though those of you who remember the book have likely never forgotten these scenes, which are rendered vividly and endlessly) that haunted and drew us in. (And perhaps which most of us read the same way we read V.C. Andrews, missing the point entirely.) I wonder if, somehow, the book was a our preadolescent way of trying to understand the way we, all of us, must prepare to leave childhood behind and take up the various roles we feel are demanded of us, prescribed for us. We must start donning the mask, and then another, and then another. And we want to see how it’s done.